Uganda’s Parliament and the shadow of bribery

By James Kabengwa

Parliament is, once again, shrouded in allegations of financial inducements to pass a controversial legislation.

Reports suggest that MPs from the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) and select opposition members received Shs100m each as “appreciation” for passing the contentious Coffee Bill last year and to secure support for proposed amendments to the UPDF Act.

These allegations, unproven yet though, are disturbingly familiar in Uganda’s political landscape and demand urgent scrutiny.

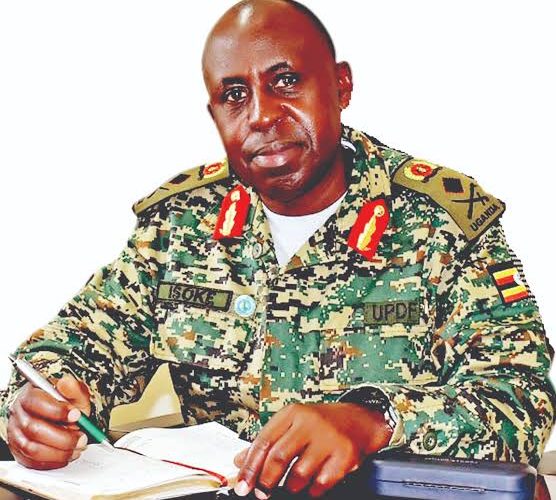

The UPDF Act amendments, if passed, would entrench military court jurisdiction over civilians, further eroding constitutional safeguards- undermining judicial independence and risks normalizing militarized justice.The UPDF among others seeks to legitimize the trial of civilians in military courts, defying a 2023 Supreme Court ruling that declared such trials unconstitutional.

Meanwhile, the Coffee Bill, ostensibly designed to regulate the sector, faced backlash for centralizing control under the Uganda Coffee Development Authority, sidelining small farmers.

The militarization of justice and the exploitation of the coffee policy is not mere legislative issues—it is an existential threatsto democracy. Allowing military courts to try civilians strips citizens of due process, while monopolizing coffee trade risks impoverishing rural communities. When lawmakers prioritize personal enrichment over these stakes, public trust evaporates.

In an X post on Tuesday, the leader of opposition, Joel Ssenyonyi claimed that cash incentives were deployed to fast-track both bills, with lawmakers allegedly swayed by personal gain rather than public interest.

This is not an isolated incident. Our Parliament has long grappled with accusations of bribery to pass laws. In 2014, in the infamous Oil Bribery Scandal, MPs were accused of accepting bribes to influence the Petroleum Bill which governed oil revenue sharing. A parliamentary investigation named several legislators, though no convictions followed.

Shs29m was reportedly dished to MPs to pass the 2017 Age Limit Bill into law-handing President Museveni a chance to rule indefinitely. Opposition MPs boycotted, citing coercion and were beaten by Special Forces in the House.

The 2020 COVID-19 Funds Misappropriation also allegedly saw MPs implicated in embezzling Shs.10 billion shillings earmarked for pandemic relief, with little accountability.

These episodes reflect a systemic rot: a legislature increasingly perceived as a marketplace where laws are auctioned to the highest bidder.

In 2022, MPs were said to have received Shs40m to pass a supplementary budget which had the State House gain Shs77bn in a supplementary budget. In 2011, just two months before the end of the 8th Parliament tern, MPs received Shs 20m for alleged mobilisation.

In December 2023, MPs reportedly received Shs100m each to approve a Shs5.2trillion supplementary budget.

Our Parliament has become a microcosm of the nation’s governance crisis. Despite constitutional safeguards, accountability mechanisms like the Leadership Code Tribunal and Inspectorate of Government remain toothless. The ruling NRM’s dominance, coupled with a fractured opposition, enables a culture of impunity.

Meanwhile, civil society and media—often the last line of defense—face escalating gags through laws like the *Computer Misuse Act*.

The latest bribery claims are a symptom of a governance system that rewards loyalty over integrity. Until we confront this culture of transactional politics, our laws will remain tools of oppression and enrichment, not instruments of justice.

The writer is a journalist and human rights activist